December 19, 2015

Update!: The competition has now ended and I am in 87th place on the public leaderboard out of 1,388 teams/individuals. Top 6% for my first kaggle!

Getting Started

Ever since I have known about kaggle, I have always seen it as a place where accomplished data scientists and skilled veterans of the machine learning space go to stretch their legs and dominate. However, as I continued to look through the competitions and through the forums where aspiring data scientists were asking a wide variety of questions, I realized that my preconceptions were probably holding me back from learning a lot through practical application. It is definitely one thing to read about algorithms and techniques and quite another to actually implement. Anyways, with that in mind, I figured I would jump in and get started.

Before I got started on the whats cooking competition, I had read a lot about the models that I was planning to use and had also read code from past competitions; however, jumping into the competition helped me actually get my hands dirty with models that I had only used a couple times before. More importantly, having to actually write the code myself, I got to practice being (or at least trying to be) systematic and comprehensive in my modeling decisions. Ultimately, I think the competition pushed me to not only read/learn, but also practice and be comfortable with an iterative problem solving process.

What's Cooking

The competition as mentioned before was hosted on the kaggle platform. While there were many competitions to choose from, I decided to do this cooking challenge because I was interested in learning natural language processing, which I felt like I hadn't really been able to practice. Although the competition did not require much real language processing, it was still appealing and interesting to think about how different ingredients could be used to predict the cuisine. (Most of the code for this competition is on my github. There are a few cleanup functions and exploratory scripts that I unfortunately have on another computer)

For me, the largest reason for joining this competition was to learn. More than wanting to place well on the leaderboard, I wanted to understand what I was doing with the algorithms I was using and I wanted to make educated decisions about my modeling choices. Then, if I happened to do well that would be an additional blessing. As a result, I spent lots of time learning by reading and tinkering. Instead of copying code from forums, I wanted to implement things myself, which took lots of time...lots of trial...and lots of error...

Initial decisions

To start with, my plan was to (I eventually only had time to do up to number 7, but ended up with a satisfying score):

- Start by exploring the data and summarizing the data to understand how the classes look, how the ingredients are distributed across cuisines, and start brainstorming which models I wanted to use

- Process the data so that I could use it as input into the model that I had decided to move forward with

- Build a simple baseline model upon which I could further improve

- Logistic regression was good for this problem because its a simple model compared to the other models that I could have started with...

- See if I need to change the way I was extracting features/ implement new feature extraction techniques to get more information from the data

- Fit the simple model again and tune the parameters

- Start experimenting with and tuning more complex models that make sense given the problem

- One thing that I am trying to learn more about is when to use a model given the input data because it is easy to throw a million models at a problem and see what works, but it takes experience and skill to figure out what model would work best given the nature of the data (though in averaging I use many random models because the point of the weighted averaging, as I know it, is to try to use weak learners and/or uncorrelated submission files to create a stronger learner/submission)

- Think about simple averaging by coming up with a weighted average of my submissions to see if the model performs better

- Enter into the real black box stuff where I stack and blend models to build crazy ensembles

- Some really legit stuff...

Anyways, the data comes in .json files, which python makes pretty easy to parse with the json package. As an example, the first entry in the data file looks like this

{u'cuisine': u'greek',

u'id': 10259,

u'ingredients': [u'romaine lettuce',

u'black olives',

u'grape tomatoes',

u'garlic',

u'pepper',

u'purple onion',

u'seasoning',

u'garbanzo beans',

u'feta cheese crumbles']}

Note: I did a few things to look through the data and summarize/ explore the data before I got started. Namely, I looked at the counts of the each cuisine to see if there were any biased classes, which there were, but when I set custom weighting for the classes the models didn't change much so I decided I would return to this later. Furthermore, I looked to format the data correctly because things like the registered trademark signs caused encoding problems in the input data.

Given the way the data was formatted, I wanted to separate out the cuisine as the y-variable and have the x-variables be the ingredients. This is where the initial decisions had to be made.

- How was I going to do the initial processing to set up my training data to extract features from the data?

- I could use a simple count vectorizer, which converts the words in a document (or in this case recipe) into counts or...

- binary encoding, which (if I implemented this correctly means 0 if the ingredient is not in the recipe and 1 if it is) or...

- tfidf (term frequency inverse document frequency) vectorizer to not only count but also return the normalized count based on how many times an ingredient appears in all the recipes

- Once the format of the training data was decided, how was I going to implement the vectorizer or binary encoder?

- This was a question I found myself asking because the standard vectorizer and encoder in sci-kit learn were slightly different than what I wanted to do.

I initially decided to write my own binary encoder because I thought that using a count vectorizer, though simple, would be throwing away information from the data. More specifically, I figured that, using the sample above, if my ingredients were ['romaine lettuce', 'black olives', 'grape tomatoes'...] and I used the stock count vectorizer then I would have the following as features ['romaine', 'lettuce', 'black', 'olives'...]. To me this was a problem because 'black olives' as one feature contained more information than 'black', 'olives' as two features.

- I had decided from the beginning that I wanted to start with a bag of ingredients and not a bag of words.

- Though I knew that I could customize the analyzer function in the sci-kit learn package, I wanted to start with a baseline model before moving onto more complex models.

def binary_encoding(list_of_ingredients,input_data):

'''

list_of_ingredients: a list of ingredients that has been deduplicated and represents the features (column titles of the matrix)

input_data: the data to be converted into a feature matrix

returns a sparse feature matrix

'''

pbar = ProgressBar() # progress bar to help me figure how much has been completed

aList = []

for recipe in pbar(input_data):

d = {}

d = d.fromkeys(list_of_ingredients,0) # creates a new dictionary with keys from list of ingredients with the initial value set to 0

for word in recipe:

if word in list_of_ingredients:

d[word] = 1 # if the ingredient is in the list of ingredients, then change value to 1

aList.append(d.values())

sparse_matrix = scipy.sparse.csr_matrix(aList) # create a sparse matrix

return sparse_matrix

After implementing the function above on the data, and running a simply logistic regression model on the data, I received ~0.77 on the leaderboard. Though it wasn't great it was my first submission and I was quite happy. Even through this initial phase of feature extracting, I realized that a lot of the time I spent on this competition would be on feature engineering and processing.

Moving forward

With the ~0.77 in the books, I decided it was time to start tuning and adding complexity.

The first thing that I did was write a preprocessing function to help me clean the input data. I decided that I wanted to stem the words so that 'olives' would become 'olive' because the plural shouldn't lead to two different ingredients. Then I also stripped the words of punctuation and other non-alphabetic characters. After this initial step, I decided it would be good to sort the words in the ingredient list so that ingredients like 'feta cheese crumbles' and 'crumble feta cheese' would be one feature and not multiple after the word stemming and ingredient sorting (may or may not have been necessary, but I figured given the way the data was structured it wouldn't hurt).

def preprocess(input_data):

new_data = []

pbar = ProgressBar() # Progress bar to ease the waiting

for recipe in pbar(input_data):

new_recipe = []

for ingredient in recipe:

new_ingredient = []

for word in ingredient.split():

word = re.sub('[^a-zA-Z -]+', '', word) # only keeping the letters, spaces, and hyphens

new_ingredient.append(wn.morphy(word.lower().strip(",.!:?;' ")) or word.strip(",.!:?;' ")) # strip, stem, and append the word

new_recipe.append(' '.join(new_ingredient))

new_data.append(new_recipe)

return new_data

def sort_ingredient(input_data):

new_data = []

pbar = ProgressBar()

for recipe in pbar(input_data):

new_recipe = []

for ingredient in recipe:

sorted_ingredient = ' '.join(sorted(ingredient.split(' ')))

new_recipe.append(sorted_ingredient)

new_data.append(new_recipe)

return new_data

After this preprocessing step, I move towards using tf-idf because I figured having an indication of the frequency of a certain ingredient would provide additional information as opposed to simple binary encoding. So I used the slightly modified tf-idf vectorizer from sci-kit learn. Similar to the count vectorizer, the default analyzer seemed to split up the words of an ingredient into two words because of the way that my data was being passed in. To solve this, I wrote my own analyzer function that basically parsed the ingredient list and returned the entire ingredient (with all the words) as one feature (think: ['romaine lettuce', 'black olives'] vs. ['romaine', 'lettuce', 'black', 'olives']).

Ultimately, combining the preprocessing with the tf-idf vectorizing and a logistic regession model gave me ~0.778 on the leader board (an improvement!). So the next step was to figure out how to further tune the model.

Model tuning

Modeling tuning seems to be an art in the machine learning world. This was where I felt out of my league because I did not have much experience. I had manually set complexity parameters before when pruning decision trees, but had not really experimented with changing the many parameters in the models I was using.

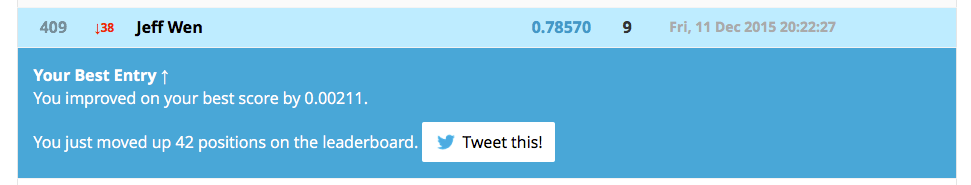

So I spent lots of time reading through the forums to see what others were doing and saw that the top performers were using grid searches. I eventually ended up using a grid search to create my strongest performing single model, but initially when I was experimenting I used cross validation to manually see how changing the regularization parameter would affect my CV scores and found that with C=5 my model was scoring around ~0.782 with the CV that I was performing on my own system. When I uploaded the submission after predicting the new cuisines I got ~0.7857 so again there was an improvement (though it was not great that my own CV was returning scores that were slightly off. I probably will spend some more time figuring out how to model a more precise evaluation metric next time.)

At this point in the competition there were around ~1000 or so competitors so I was in the top 50%, which was exciting considering just a few weeks ago I didn't even think I could create any worthwhile models.

Rethinking my initial assumptions

Initially, I had decided not to use the standard sci-kit learn vectorizer analyzers because I felt that it would take away information from my data. However, upon further consideration, I realized that it was worth a try because with > 5000 features not all the features would be important anyways so why create more features by creating a bag of ingredients if a bag of words may actually help to reduce complexity a little bit.

With this in mind, I rewrote my preprocessing function and started using the tf-idf vectorizer from sci-kit learn with a few parameters modified.

def preprocess_all_ingredients(input_data):

new_data = []

pbar = ProgressBar() # Progress bar to ease the waiting

for recipe in pbar(input_data):

new_recipe = []

for ingredient in recipe:

new_ingredient = []

for word in ingredient.split():

# using a word lemmatizer, which is related to stemming, but takes into account context also (in this case other ingredients in the recipe)

word = re.sub('[^a-zA-Z]', ' ', word)

new_ingredient.append(WordNetLemmatizer().lemmatize(word.lower().strip(",.!:?;' ")) or word.strip(",.!:?;' "))

new_recipe.append(' '.join(new_ingredient))

new_data.append(' '.join(new_recipe))

return new_data

The new function is similar to the previous preprocessing function but uses a lemmatizer instead of a stemmer (read more here), which basically takes context into account (though lemmatization may not have much use in this case given the ingredients are separate words in a string and not a cohesive sentence).

tfidf_vectorizer = TfidfVectorizer(stop_words='english',ngram_range=(1,1), analyzer='word', max_df=0.56, token_pattern=r'\w+')

With the new preprocessing and vectorizer in place, I used a logistic regression again and got ~0.787. So there was again an improvement but at this point, I figured maybe I had come close to the extent of progress I would make with the logistic regression model. I did run a grid search over the regularization parameter and received a score of ~0.788. However, I was ready to move onto other models and thought that I would perhaps come back to logistic regressions if I were to do stacking and blending of models later on.

Big improvements

The next steps in the modeling process led to huge improvements and at one point even got me to the top 3% of the leaderboard.

At this time the top performers seemed to be using neural nets and xgb models (extreme gradient boosted trees). I tried xgb but my results were not great (the best xgb gave me ~0.78).

With the basic preprocessing functions set, I felt like I should spend more time on reading and understanding how to tune my models. I had used support vector machines (SVM) before, but I was unsure if the model would handle the data given that my computer is old and SVMs are not known to perform particularly quickly if the dataset is too large. Given that I had thousand of features, I was afraid of the run time of using SVMs, but in the end after reading a couple resources (including this one) I decided I would give it a try and just change to something else if necessary. Furthermore, SVMs have fewer hyperparameters to tune (so it would be easier to set up a grid search compared to say xgb or neural nets).

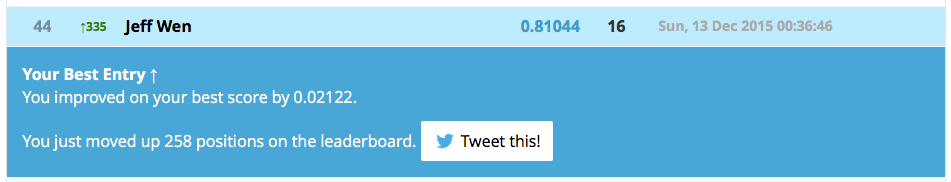

param_grid = [{'C': [0.1, 1, 10], 'kernel': ['linear']},{'C': [0.1, 1, 10], 'gamma': [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1], 'kernel': ['rbf']}]

I tried both linear and non-linear kernels and a variety of regularization parameters (I tried to read a lot on how to choose the parameters to place in the grid search). After fitting the model, which took at least 8 hours, I took a look at the parameter grid, which also shows the CV scores from the 3-fold CV that was performed in the grid search and noticed that the scores were pretty varied, but some scores were > 0.80. Of course I was excited, but not ecstatic because I knew that my CV was not exactly in line with the Kaggle leaderboard score calculation. When I submitted, I was surpised to see that my submission received a score on the leaderboard of ~0.81044 (HUGE improvement for me!).

At this point there were ~1200 teams in the competition so my score put me somewhere in the top 3%! I was originally okay with the top 50%...but no complaints!

Finishing touches

With only a couple days or so left in the competition, I didn't have much time to run additional stacked models or try tuning neural networks. However, I knew that I could squeeze a little more out of my submissions and so I spent some time researching stacking and blending of models. I had read that many recent winners had performed so well because they had implemented some form of stacking and/or blending (the netflix prize was won by an ensemble of 800 different models). Of course, basic understanding of what each model is doing is very important and was my main goal, but at this point I felt like I could do little more.

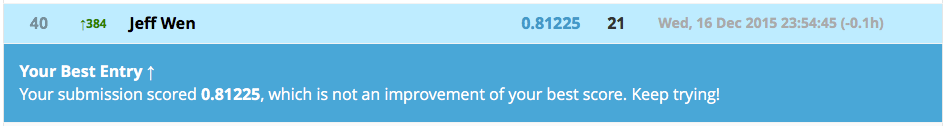

I basically ended up doing a weighted average of my top submission files (which is not stacking or blending but a precursor step). In particular, I gave my SVM 3x weight, logreg 1x, linear SVC 1x, another logreg 1x, and extra trees classifier 1x and ended up with a score of ~0.81225, which at the time placed me at 40th out of ~1300 teams.

Lots to learn

It has been such a journey starting with importing the .json files to getting (at the time) 40th on the leaderboard. Even though with a few more hours to go in the competition I figure I may drop a few places, I feel like I have gained at least a taste of what it feels like to enter and apply the things that I have learned.

In entering this competition I got a chance to apply a lot of things that I had read about. Furthermore, I read EVEN MORE things that I didn't get to try out but hope to in the future. I have listed a few take-aways and things to try in the future.

Next steps

- Use Levenstein distance to map similar words together (I actually have a function in my cooking code that I was going to use, but I never got around to implementing it...)

- Use Bayesian Optimization or Random Search to optimize parameter settings

- Stack and blend different models

- Experiment with other models (i.e. neural networks, xgb (with good parameter tuning))

Take-aways

- Parameter tuning is very important and though grid search worked out well this time, its really computationally intensive and in another setting I might not have the luxury to perform this type of exhaustive search. I can try random search, which may be better but a very interesting thing that I read about were two packages called: Spearmint and Hyperopt, which use bayesian optimization to perform the parameter search (read this awesome blog post or this one to learn more about parameter tuning and bayesian optimization)

- Fitting models is easy, but figuring which model to use and when is difficult

- The need for a representative cross validation evaluation metric is very important if you want to know how your model is performing. I think this is why some teams spend quite a bit of time writing their own evaluation function that matches the competition's evaluation function because if they tell you how you will be judged why not use it!

- Simple models can actually perform really well when tuned properly. Given that simple models are MUCH faster to train it may be better to use a simple model if the application does not require absolute accuracy (this really depends on the problem at hand; healthcare is not an area where we want to use less accurate models just to speed up the modeling process)

- The entire problem solving approach has to iterative.

- Feature engineering and preprocessing take lots of time but are very important! I think this is where industry domain becomes handy because if I knew more about cooking I might have been able to create some more informative features

The End!

There are a lot of things that I have left out of this post in regards to my process and thinking but if there are any questions feel free to email me! I hope that this is just a start of my continued learning through kaggle and similar platforms.